Forty years ago this week, FBI agents raided a safe house on Whidbey Island that led to a standoff with Robert Mathews, the leader of a white supremacist movement born in the Inland Northwest.

Mathews refused to surrender peacefully. A machine- gun fight ended with the house ablaze, Mathews still inside.

“The Order,” a new crime thriller released next Friday, directed by Justin Kurzel and starring Jude Law and Nicholas Hoult, is based on true events leading up to that showdown.

The Silent Brotherhood, more commonly known as The Order, was a radical schism that broke off from the Aryan Nations, a neo-Nazi compound that was based near Hayden Lake.

The movie draws out the tension between Mathews, played by Hoult, and Aryan Nations leader Richard Butler, who insists on working within the system to gain power by getting politicians elected. Mathews grows impatient with Butler’s talk and no action. So, Mathews takes action. His new followers help him rob a Washington Mutual bank branch at gunpoint in Spokane.

Meanwhile Law’s character, hardboiled FBI agent Terry Husk, arrives in Coeur d’Alene, tasked with reopening a field office by himself. He enlists the help of the Kootenai County Sheriff’s Office and befriends a young deputy, played by Tye Sheridan.

“In my experience, hate groups don’t rob banks,” Husk says.

“Maybe this time is different,” the deputy replies. The screenplay is based on “The Silent Brotherhood: Inside America’s Racist Underground,” a 1989 nonfiction book by Denver journalists Kevin Flynn and Gerhardt. The co-authors covered the case for The Rocky Mountain News beginning with The Order’s assassination of Alan Berg, a provocative Denver radio talk show host who was Jewish.

Comedian-podcaster Marc Maron plays Berg in the film.

It’s not the first movie adaptation of the story. The 1988 film “Betrayed,” starring Tom Berenger, is a highly fictionalized version set in the Midwest. That same year, Oliver Stone’s “Talk Radio” focused on a character inspired by Berg and his assassination.

“The Order” is a truer tracking of the crimes committed across the Northwest.

Filmed in Alberta, the movie evokes a vaster, less developed North Idaho.

The real Terry Husk

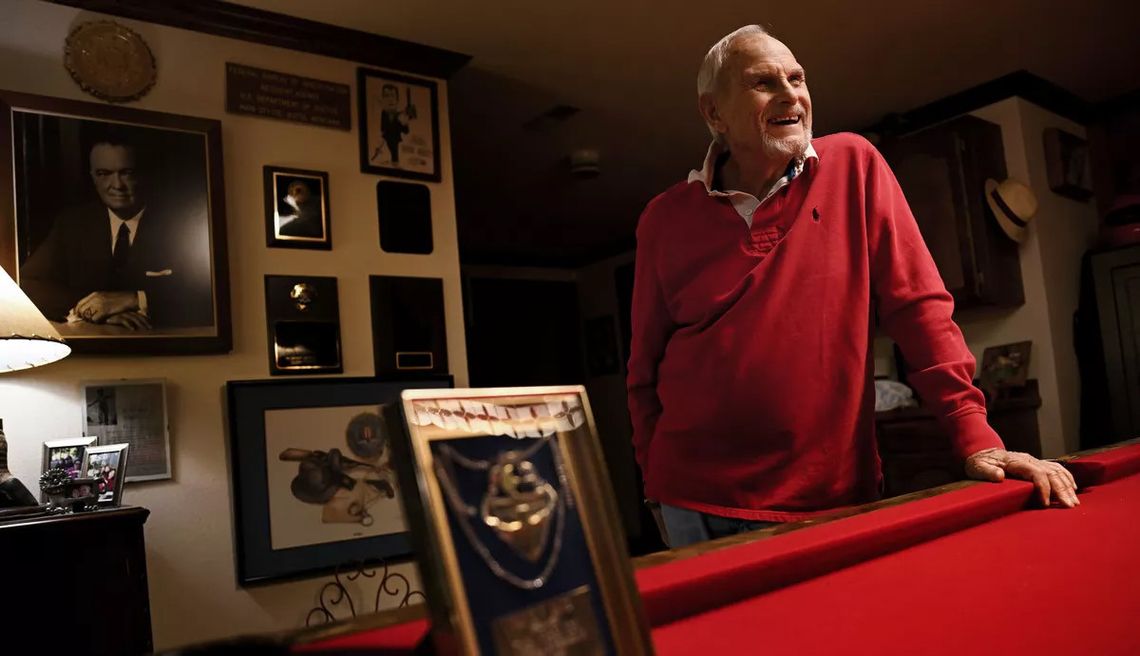

While Husk is fictional, his actions are certainly based on former FBI agent Wayne Manis, who still lives at the home he built in 1984 not far from the Aryan Nations compound.

The first two words of “The Silent Brotherhood,” he proudly points out in an interview with The Spokesman-Review, are “Wayne Manis.” His main complaint about the movie?

“I don’t smoke,” Manis said. Law, who produced the film, said in an interview with FRED Film Radio that the filmmakers decided to make Husk fictional so they could use him as a flawed character.

“We wanted him to represent certain characteristics of society within the story,” Law said. “It helped an awful lot. It meant we were really free to sort of create Husk in any way we needed him to lean. The fragility, the physicality, the smoking, the drinking, the fatigue, the shattered family, all of that we were able to slowly piece together as opposed to, ‘Look at what really happened and who was involved.’ ” Manis, now 84, moved to Idaho from Alabama in February of the year the film takes place, ahead of his wife and daughter, who joined him that summer. Ten months later, he was in the standoff with Mathews.

His daughter, Christa Hazel, said that watching the film reminded her how intense that year was for the family. She was 10 years old.

“It wasn’t uncommon to not hear from him from time to time,” said Hazel, a former Coeur d’Alene School Board member. “So, I won’t forget the phone call from Whidbey Island where he called to let us know he had been in a shootout, but he was OK. We would probably see it on the news, but he needed us to know he was OK.”

This wasn’t Manis’ first rodeo. Before Idaho, he was an undercover agent who investigated left-wing extremists, the Mafia and the KKK.

One time he was arrested while undercover in Chicago, and was bailed out, unwittingly, by the Communist Party.

Manis retired in 1994. He writes all about his career, including The Order, in his memoir, “The Street Agent.”

Reign of terror

Manis said the film does a good job including all the major crimes committed by Mathews and his followers, even if some of the scenes and characters are conflated.

“I am glad it is being showed, because even though it’s Hollywood, maybe it will bring back an awareness of how serious this really was,” Manis said.

After splitting with Butler, Mathews based his faction at his farm in Metaline Falls in the northeast corner of Washington. But his influence was far-reaching.

One of their first acts of terrorism was to test a homemade bomb at a Boise synagogue, although the device did little damage to the building, and no one was in inside when it went off.

The film shows Mathews following a playbook outlined in “The Turner Diaries,” a 1978 novel by white nationalist William Pierce that depicts a group also called The Order as overthrowing the U.S. government.

A postscript at the end of the film ascribes “The Turner Diaries” as also influencing the Oklahoma City bombing and elements of the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

In the film and real life, Mathews’ Order pulled off a series of heists against banks and armored cars. But it began with a simple job, not in the film: robbing an adult video store in Spokane Valley. They stole $369.

Over the ensuing months, they hit bigger and bigger targets in Spokane, and Seattle, where they bombed an adult movie theater as a diversion.

It culminated in a $3.8 million robbery of a Brink’s armored car on a highway in Northern California near Ukiah.

Along with counterfeiting, the money was meant to finance their higher ambitions: to establish a separate white nation in the Pacific Northwest. Other plots were to destroy the Los Angeles power grid and poison the water supply.

After Mathews’ death, 10 members of The Order were convicted on racketeering and conspiracy charges, and some received sentences exceeding 100 years. Two others were convicted for violating Berg’s rights by killing him.

Manis pointed out a few ways the movie differs from history.

One of them involves the fate of Husk’s deputy.

In another, Husk discovers the body of Walter West, a member of The Order who was shot in the woods for speaking openly about their activities. But the body was never found, Manis said. It’s a loose end that still troubles him.

At the end of the movie, Husk runs into the burning house to try to persuade Mathews to come out. Frankly, Manis said, he wouldn’t have done that.

For Kevin Flynn, the book author, the film’s inconsistencies don’t bother him a bit. It gets the bigger point right: the threat posed by white nationalism.

Flynn, who is now a sitting Denver city councilman, said he wanted to write the book to tell the deeper story beyond the daily headlines he was writing. He wanted to answer the questions: Who were these people and how did they become so radicalized?

It turned into a meticulous profiling of about 40 people associated with the organization. With a few exceptions, they didn’t have criminal records. For most of them, Flynn said, if they had never met Mathews, they wouldn’t have done any of it.

“This guy was very charismatic,” Flynn said.

Flynn consulted on the movie and was impressed with how authentic the cast and crew wanted it to be.

His co-author, Gary Gerhardt, died in 2015. Flynn said Gerhard always thought it would make a good movie, as a cops-androbbers true crime narrative. He spread some of Gerhardt’s ashes on the film set and at the premier at the Venice Film Festival.

The everlasting threat

In “The Silent Brotherhood,” Flynn republished a picture by Spokesman-Review photographer John Kaplan of Mathews confronting a woman protesting an Aryan Nations rally held in Riverfront Park in June 1983.

The woman held a sign that said, “Destroy racism.”

“What we are saying in the book is there is no end to racism, I’m sorry to say,” Flynn said. “It has been around for millennia, it is never going to end, it is going to have to be confronted constantly. That was the frightening conclusion Gary and I reached.” Manis agreed. He paraphrased something he said David Lane, a prominent member of The Order, said after he was imprisoned – that the concept of The Order still existed, and it would only take a spark to bring it back. “I’ve always thought about that,” Manis said. “This could happen again.” Even today, there are people living in the area who view The Order in a favorable light, he said. Today, Manis’ home overlooking Hayden Lake is like a museum. Inside, taxidermy African beasts stand as trophies from past safaris.

A recurring motif in the film has Husk’s character hunting an elk but hesitating to shoot. This is juxtaposed against encounters between Husk and Mathews, where they also hesitate to shoot one another.

But Manis, a hunter at heart, wouldn’t have hesitated to shoot the elk.

“The Order” is exclusively in theaters beginning Dec. 6.

JAMES HANLON’S REPORTING FOR THE SPOKESMAN- REVIEW IS FUNDED IN PART BY REPORT FOR AMERICA AND BY MEMBERS OF THE SPOKANE COMMUNITY. THIS STORY CAN BE REPUBLISHED BY OTHER ORGANIZATIONS FOR FREE UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE.

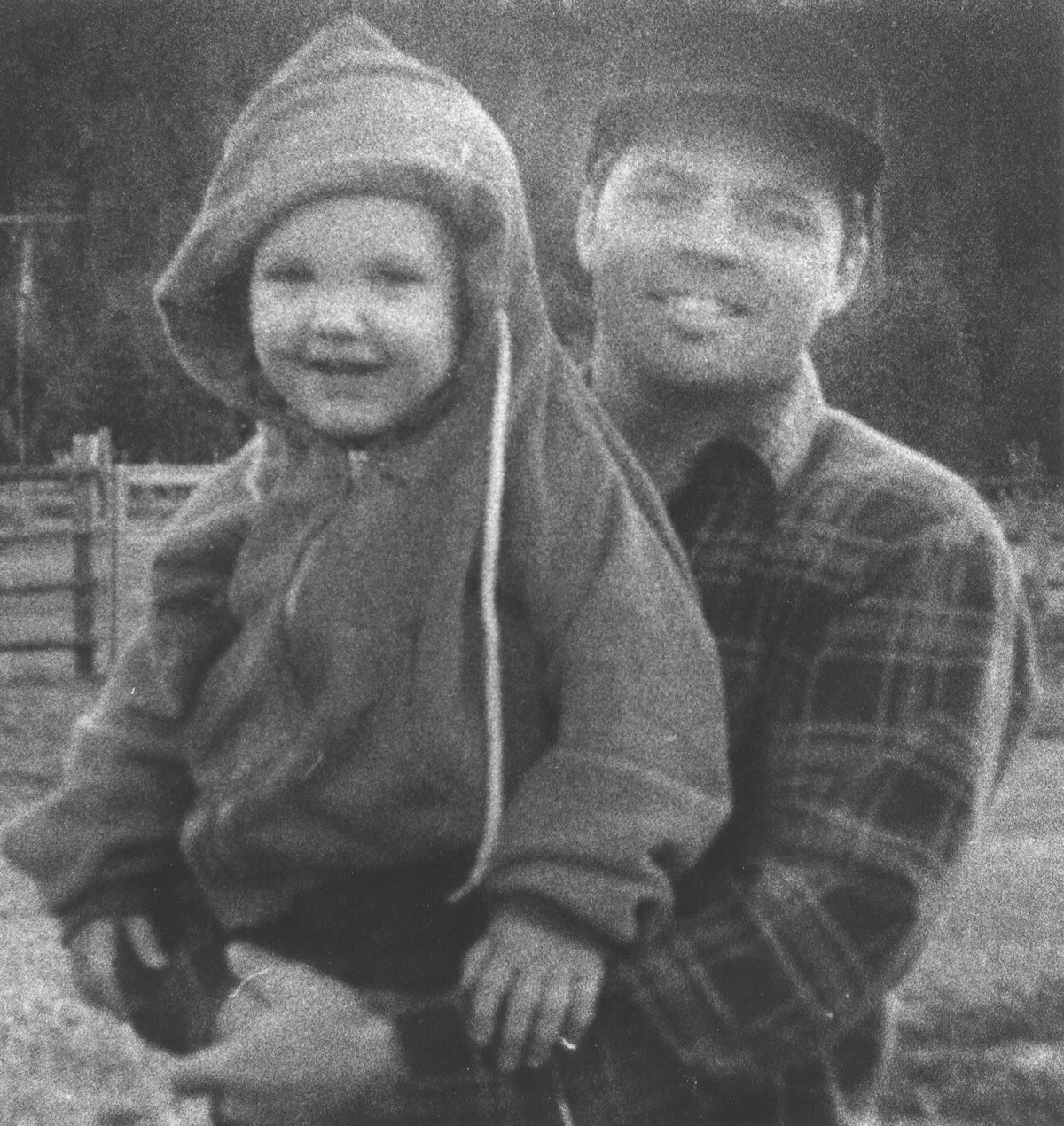

Robert Mathews and 3-year -old son Clint in the ‘80s. (The Spokesman-Review archive)

.png)